The Computer I Never Built

There lurks in the lab the ghost of a mainframe

Duane Couchot-Vore

Content:

I'm sure I was ahead of most second-graders when it came to understanding computers. I was an early reader, and one day when Dad took me to the Cincinnati library, I came back with a book on them. Analog computers were still a thing then, but those made less sense to me than Greek, probably because I hadn't yet been exposed to logarithms, integrals, and Laplace transforms. Digital computers, on the other hand, were just logic, and that I understood. Half adders, shift registers, and instruction sets made perfect sense to me. Those were the days when having a computer in your home was judged just as practical as having a cyclotron, but that didn't stop me from wanting one. Several times during my youth, I attempted to design one. (I sort of wanted a cyclotron, too.)

Then came the day when I was at Radio Shack, my second home, whereupon I found a keyboard. Not a USB keyboard, nor even a PS/2 keyboard, as those did not yet exist. Just a keyboard. A set of switches laid out like a typewriter with letters on the top and switch connections on the bottom. That seemed like the perfect starting point for the ultimate computer. I bent a piece of aluminum into a mounting plate at a comfortable typing angle and mounted the keyboard on top. Beneath that was a roughly 10x15 cm piece of Vectorboard loaded with TTL, a 1702 EEPROM, and whatever else I needed to make it all work. At the end of that project I could type on it and have it spit out ASCII over an RS-232 interface.

Next, I needed a monitor. A larger piece of Vectorboard and even more TTL, lots of it organized as a complex synchronous counter to generate television timing pulses and to scan the ram and character generator EEPROM. I scrounged a 9" monochrome monitor from Mendelson's, which was the go-to place for electronics surplus in Dayton in those days. I suspect it was intended as a monitor for a CCTV security system, but I wasn't interested in one of those. I doubt that I implemented all the control codes because those would have to have been done in hardware, but I had the essentials and some way to position the cursor. The details are long forgotten. At that point, I could type on the keyboard and have it show up on the monitor. Not very useful yet, but fun to show people.

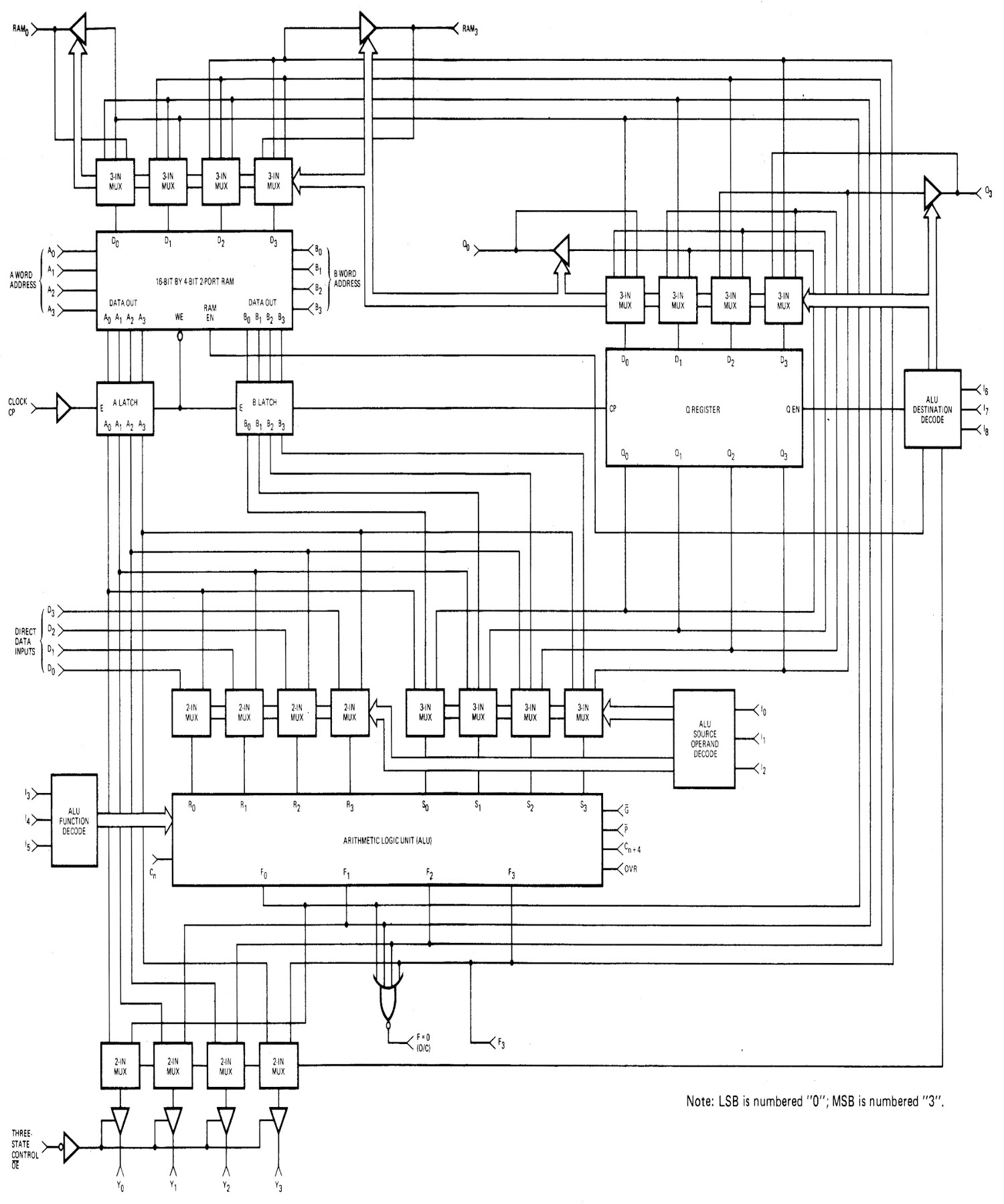

Then came the big boy. Armed with a stack of 9"-by-12" breadboards and and handful each of AMD Am2901s and some 64x4 RAMs, I started building. I learned later that the Am2901-family bit-slice components formed the basis of several mainframe computers, so I was on the right track. That particular segment would be the ALU board. I planned a microprogram control board, a hardware multiply board, a memory access board, and I had dreams at least of a floating-point unit. What worried the most was memory. Semiconductor memory existed, but it was expensive, and I didn't look forward to wiring up thousands of ferrite cores. An array of 64 by 64 cores would be 4096 bits, and 32 of those would still only be 16kB. I didn't even have a plan to thread cores; it sounded worse than crocheting. But I steamed ahead anyway, supposing a memory solution would present itself along with the forward march of technology. The computer was to have some innovative features such as a hardware random number generator based on quantum noise, and special registers to speed up loops. I can't remember what all.

Unfortunately, I wasn't the engineering staff of DEC or IBM. I was just me, working in my spare time aside from the lab that paid my salary. And that, indirectly, was what stopped me. Not that it would take a long time or that the design would be complex. It was the arrival of Intel 80286. In the blink of an eye, the world had gone from 8 bits at 3MHz to 16 bits at 12Mhz. It became suddenly obvious that before I could finish my machine, there would be 32-bit microprocessors surpassing my planned 20Mhz by a significant margin.

So my home-built mainframe was dead. Alas! It's one of the skills of an engineer to know when something is impractical. To continue was just impractical. But at least I had some fun and could type on a monitor. Unfortunately, I didn't keep anything very long and never took any pictures. I was bad about that.

But my prediction came true. The National 32032 soon made its appearance, and then I was in love with that. Almost everything I had planned to do in the size of a postage stamp, and with a lot less effort on my part.